Human genetics holds the key to understanding everything from physical traits to inherited diseases. As we dive into the complexities of how genes shape our biology, we encounter various tools and methods that help decode the inheritance of traits and the mechanisms behind genetic disorders. In this blog, we’ll explore key concepts like pedigree analysis, LOD scores for linkage testing, karyotyping, and the intricate world of genetic disorders.

Pedigree Analysis: Tracing Family Traits Through Generations

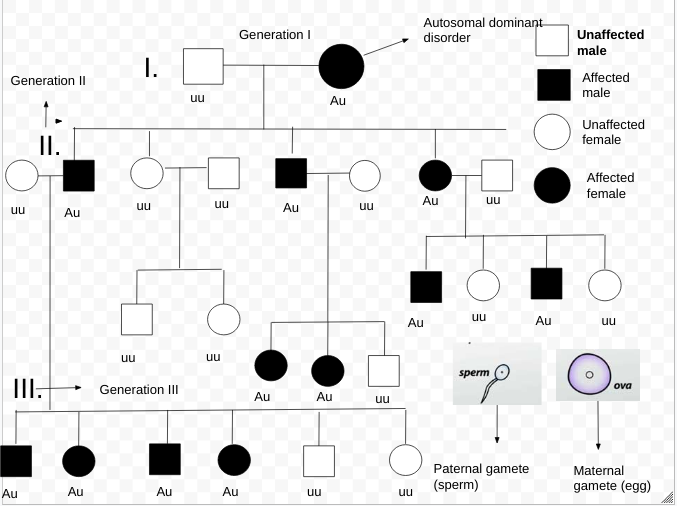

Pedigree analysis is a fundamental tool in human genetics. It’s like a family tree but focuses on the inheritance of specific traits, particularly genetic disorders. This method allows geneticists to track how traits are passed from one generation to the next, providing insights into whether a condition is dominant, recessive, autosomal, or sex-linked.

How Pedigree Analysis Works

A pedigree chart uses standard symbols to represent family members and their relationships. Males are typically shown as squares, females as circles, and the presence of a genetic trait is marked by shading in the corresponding shapes. By analyzing the distribution of a trait in the family, geneticists can determine the mode of inheritance and assess the risk of passing it on to future generations.

For example, if a disorder appears in every generation and affects both males and females equally, it is likely to be an autosomal dominant trait. In contrast, if the disorder skips generations and is more common in one gender, it might be autosomal recessive or sex-linked.

Why Pedigree Analysis Matters

Pedigree analysis is crucial for understanding genetic risk factors in families. It is widely used in genetic counseling to help families assess the likelihood of passing on genetic disorders to their children. It also aids researchers in identifying patterns of inheritance and can be combined with modern genetic testing to pinpoint specific genes responsible for certain conditions.

LOD Score for Linkage Testing: Measuring Genetic Distance

Understanding how genes are inherited together is key to mapping human chromosomes. The LOD (logarithm of odds) score is a statistical tool used to test for linkage between genes. Linkage occurs when genes are located close to each other on the same chromosome and are inherited together more often than by chance.

How LOD Score Works

The LOD score compares the likelihood that two genes are linked versus the likelihood that they are not linked. A positive LOD score suggests that genes are likely linked, while a negative score indicates they are inherited independently.

A LOD score of 3.0 or higher is considered strong evidence of linkage. This means there is a 1,000:1 likelihood that the genes are inherited together, making it an essential tool for genetic mapping.

Linkage Testing and Genetic Disorders

LOD scores are often used to locate genes responsible for genetic disorders. By studying families with a known history of a disorder, geneticists can determine whether a gene for the disorder is linked to a specific marker on the chromosome. This is a crucial step in identifying disease-causing genes and understanding the genetic architecture of complex traits.

Attribution: Rainger J, van Beusekom E, Ramsay JK, McKie L, Al-Gazali L, Pallotta R, et al., CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia CommonsKaryotypes: Visualizing Chromosomes for Genetic Diagnosis

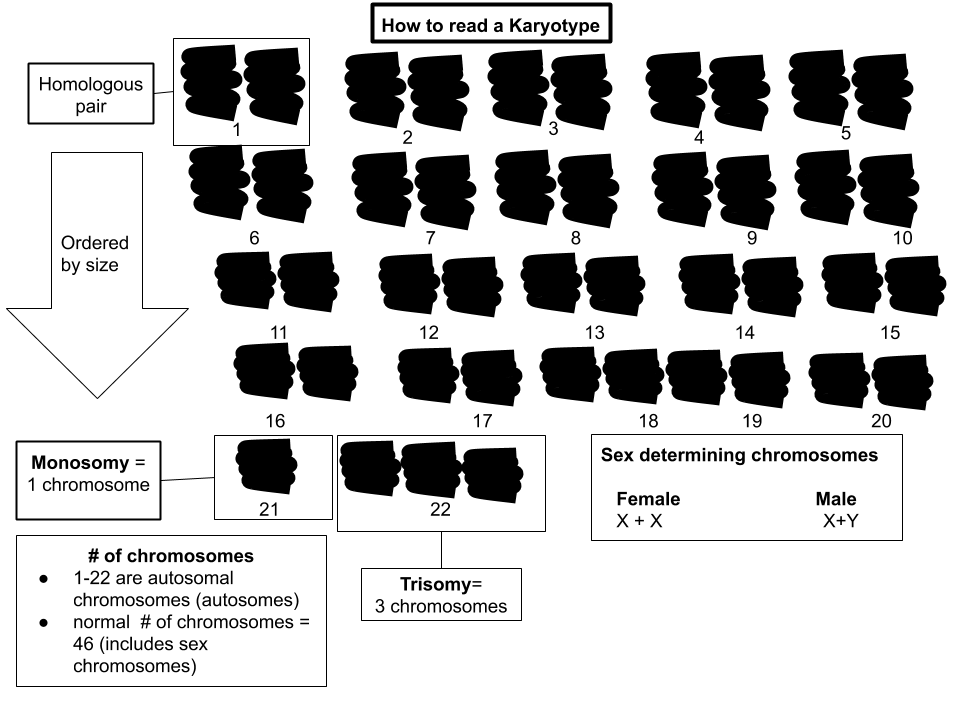

A karyotype is a visual representation of an individual's chromosomes. This method involves staining chromosomes and arranging them in pairs, from largest to smallest, allowing geneticists to examine the structure and number of chromosomes in a person’s cells.

|

| Fig.- Human male Karyotype after G-banding. Attribution- Courtesy: National Human Genome Research Institute, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

How Karyotyping Works

Cells are typically collected from blood, amniotic fluid, or other tissues. After staining, the chromosomes are photographed under a microscope, and the image is arranged to show the 23 pairs of human chromosomes. Geneticists then analyze the karyotype for abnormalities, such as extra or missing chromosomes, or structural changes like translocations, deletions, or duplications.

Why Karyotyping is Important

Karyotyping is a critical tool for diagnosing chromosomal disorders. One of the most well-known examples is Down syndrome, which occurs when an individual has an extra copy of chromosome 21. Karyotyping can also detect conditions like Turner syndrome (where a female is missing one X chromosome) and Klinefelter syndrome (where a male has an extra X chromosome).

In addition to diagnosing chromosomal abnormalities, karyotyping is used in prenatal testing, cancer diagnosis, and fertility studies, making it an essential tool in both clinical and research genetics.

|

| Attribution: Dmonlrd, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Genetic Disorders: Unraveling the Causes of Inherited Diseases

Genetic disorders are diseases caused by changes or mutations in an individual’s DNA. These disorders can range from single-gene mutations to complex conditions involving multiple genes and environmental factors.

There are several categories of genetic disorders:

Single-Gene Disorders: Caused by mutations in one gene. Examples include cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia, and Huntington's disease.

Chromosomal Disorders: Result from abnormalities in the number or structure of chromosomes, such as Down syndrome or Cri du Chat syndrome.

Multifactorial Disorders: Involve mutations in multiple genes, often in combination with environmental factors. Heart disease, diabetes, and cancers fall into this category.

Mitochondrial Disorders: Caused by mutations in mitochondrial DNA. These are relatively rare and often affect energy production in cells.

How Genetic Disorders are Inherited

The way genetic disorders are inherited depends on the nature of the mutation and whether it is located on an autosomal chromosome or a sex chromosome. For example, autosomal dominant disorders require only one copy of the mutated gene to cause the disease, while autosomal recessive disorders require two copies (one from each parent).

Sex-linked disorders are typically associated with mutations on the X chromosome. Since males have only one X chromosome, they are more likely to express the disorder if they inherit the mutated gene. In contrast, females are often carriers because they have a second, normal X chromosome that can compensate.

Gene Therapy and Genetic Engineering

As our understanding of genetic disorders grows, so too does the potential for treating them. Gene therapy involves inserting, altering, or removing genes within an individual’s cells to treat disease. Although still in its early stages, gene therapy has shown promise in treating disorders like hemophilia, muscular dystrophy, and certain forms of blindness.

CRISPR-Cas9 technology, a tool for gene editing, offers even more potential. By allowing scientists to precisely modify the DNA sequence, CRISPR holds the promise of correcting genetic mutations at their source, potentially offering cures for inherited diseases.

|

| Attribution: Reghupaty, S.C.; Sarkar, D., CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Conclusion: The Future of Human Genetics

Human genetics is an ever-evolving field that helps us understand the biological blueprint that makes us who we are. Through pedigree analysis, we can trace family traits and predict the risk of inherited diseases. LOD scores provide the tools to map the human genome and understand how genes are linked, while karyotyping helps us visualize chromosomes and detect genetic abnormalities.

At the heart of this field is the study of genetic disorders, which not only illuminates the challenges of inherited diseases but also points the way to future therapies through gene therapy and gene editing.

As science continues to unlock the secrets of our DNA, the potential to diagnose, treat, and even prevent genetic disorders becomes ever more possible, offering hope for a future where inherited diseases are a thing of the past.