Microbes may be small, but their impact on our world is massive. These tiny organisms, such as bacteria, are everywhere, influencing everything from human health to ecosystems. What makes bacteria so fascinating is not just their omnipresence but also their incredible adaptability. Part of their adaptability comes from their unique ability to exchange and manipulate genetic material in ways that differ vastly from how larger organisms like us do. Instead of sexual reproduction, bacteria rely on a variety of mechanisms to transfer genes, making them masters of evolution and survival.

In this post, we’ll explore the fascinating world of microbial genetics and focus on the different ways bacteria transfer their genes, specifically transformation, conjugation, transduction, and sex-duction. We’ll also touch on how these processes help researchers map bacterial genes through techniques like interrupted mating and fine structure analysis.

|

| Attribution: 2013MMG320B, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

What is Microbial Genetics?

Before diving into the details of genetic transfer methods, let’s first take a moment to understand microbial genetics. Bacteria don’t reproduce sexually like humans or other animals. Instead, they transfer genetic material horizontally through various mechanisms, which allows them to rapidly acquire new traits that can help them survive in different environments. This is especially true in harsh conditions where adaptability is key.

Bacteria have two primary types of DNA:

- Chromosomal DNA: A circular chromosome that contains essential genes.

- Plasmid DNA: Small, circular DNA molecules that carry extra, but often advantageous, genes, like those for antibiotic resistance.

Bacteria use several unique ways to transfer these genes from one individual to another. Let’s take a closer look at each method.

|

| Attribution: Nejash Abdela, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Transformation: Picking Up Naked DNA from the Environment

One of the simplest ways bacteria can acquire new genetic material is through transformation, where they take up naked DNA from their surroundings. This process was discovered by Frederick Griffith in the 1920s when he observed that harmless bacteria could be transformed into deadly ones by taking up DNA from dead, pathogenic bacteria.

How Transformation Works

Bacteria must be in a state of competence to undergo transformation, meaning they are able to bind and take up DNA. Not all bacteria are naturally competent, but some, like Streptococcus pneumoniae and Bacillus subtilis, can easily take up DNA from their environment.

When bacteria take in this DNA, it either integrates into their chromosome or remains as a separate plasmid, giving them new capabilities, such as resistance to antibiotics or the ability to metabolize new substances.

|

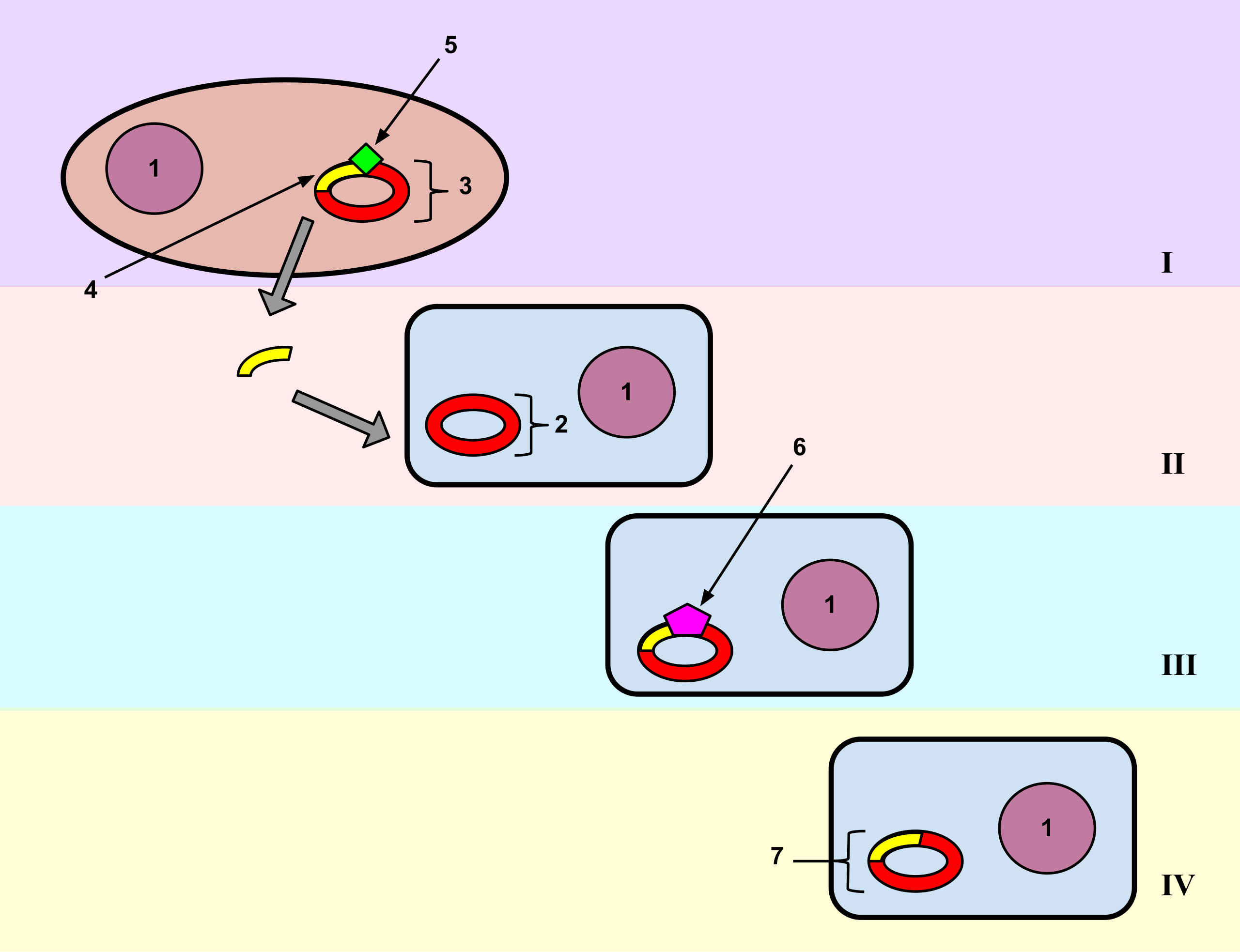

Fig.- Bacterial Transformation: Step I: The DNA of a bacterial cell is located in the cytoplasm (1), but also in the plasmid, an independent, circular loop of DNA. The gene to be transferred (4) is located on the plasmid of cell 1 (3), but not on the plasmid of bacterial cell 2 (2). To remove the gene from the plasmid of bacterial cell 1, a restriction enzyme (5) is used. The restriction enzyme binds to a specific site on the DNA and “cuts” it, releasing the satisfactory gene. Genes are naturally removed and released into the environment usually after a cell dies and disintegrates.

Step II: Bacterial cell 2 takes up the gene. This integration of genetic material from the environment is an evolutionary tool and is common in bacterial cells. Step III: The enzyme DNA ligase (6) adds the gene to the plasmid of bacterial cell 2 by forming chemical bonds between the two segments which join them together. Step IV: The plasmid of bacterial cell 2 now contains the gene from bacterial cell 1 (7). The gene has been transferred from one bacterial cell to another, and the transformation is complete. Attribution: Sprovenzano15, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Why Transformation Matters

Transformation allows bacteria to rapidly evolve. For instance, if a bacterium acquires a plasmid that carries genes for antibiotic resistance, it can survive and thrive in environments where antibiotics would normally kill it. This is a big concern in the medical world, as it contributes to the rise of antibiotic-resistant infections.

|

| Attribution: Rosanna Hartline (RosieScienceGal), CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Conjugation: Bacteria Mating Through Direct Contact

While transformation involves taking up free DNA, conjugation is a method of genetic transfer that requires direct contact between two bacterial cells. This was discovered by Joshua Lederberg and Edward Tatum in the 1940s and is often referred to as bacterial "mating."

|

Attribution: Adenosine, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

How Conjugation Works

In conjugation, a donor bacterium transfers genetic material to a recipient. The donor must have a specific piece of DNA called the F plasmid (also known as the fertility plasmid), which allows it to form a pilus, a bridge-like structure that connects to the recipient bacterium. Once connected, the donor bacterium can transfer a copy of the F plasmid to the recipient, turning it into a donor as well. Along with the F plasmid, the donor can also pass on other plasmids or segments of its chromosomal DNA.

The Spread of Antibiotic Resistance

One of the most significant outcomes of conjugation is the spread of antibiotic resistance genes. Since these genes are often located on plasmids, they can easily be transferred from one bacterium to another through conjugation, speeding up the spread of resistance across bacterial populations—even between different species.

Transduction: Viruses as Genetic Couriers

Another fascinating method of genetic transfer in bacteria is transduction, where bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) carry genetic material from one bacterium to another. This process, discovered by Norton Zinder and Joshua Lederberg in the 1950s, shows how viruses can facilitate the exchange of genes between bacteria.

en.svg/1258px-Transduction_(genetics)en.svg.png) |

| Attribution: Reytan with modifications by Geni, Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsA |

How Transduction Works

There are two types of transduction: generalized and specialized.

In generalized transduction, when a bacteriophage infects a bacterium, it sometimes mistakenly packages bacterial DNA instead of viral DNA into new virus particles. These phages then transfer the bacterial DNA to the next bacterium they infect.

In specialized transduction, the bacteriophage integrates its DNA into the bacterial chromosome. When the phage later exits the bacterial DNA to form new virus particles, it may take a portion of the bacterial genes with it. This viral-bacterial DNA is then passed to the next bacterium the phage infects.

Why Transduction Matters

Transduction allows bacteria to exchange genes in a highly efficient way. This is particularly important in the spread of traits like toxin production or antibiotic resistance across different bacterial species, which can pose significant challenges in medicine and agriculture.

Sex-Duction: Transfer of F’ Plasmids

Sex-duction, also called F' conjugation, is a variation of conjugation where the F' plasmid—an altered version of the F plasmid that carries extra chromosomal DNA—gets transferred from one bacterium to another.

How Sex-Duction Works

In sex-duction, the donor bacterium carries an F' plasmid, which not only has the genes for conjugation but also carries additional chromosomal genes from the donor. When the F' plasmid is transferred to the recipient bacterium, the recipient inherits both the plasmid and the donor's chromosomal DNA.

Why Sex-Duction is Important

Sex-duction is a useful tool in laboratory research, allowing scientists to introduce specific genes into bacterial populations for study. This method is particularly valuable in genetic mapping and experiments designed to understand gene function.

Gene Mapping Through Interrupted Mating

One of the key techniques in bacterial genetics is gene mapping, and one of the most ingenious ways to map bacterial genes is through a process called interrupted mating.

How Interrupted Mating Works

In interrupted mating, a donor bacterium that has an integrated F plasmid (called an Hfr strain) transfers its chromosomal DNA to a recipient F- cell. The DNA transfer happens in a linear fashion, starting with the genes closest to the F plasmid integration site. By interrupting the mating process at specific time intervals, researchers can identify which genes were transferred before the interruption.

This method allows scientists to create a linkage map of the bacterial chromosome, showing the relative positions of genes based on the order in which they are transferred.

Why Interrupted Mating Matters

Interrupted mating revolutionized the field of microbial genetics by allowing scientists to map bacterial chromosomes and understand the genetic layout of organisms like E. coli. These maps have been instrumental in studying gene function, mutation rates, and bacterial evolution.

Fine Structure Analysis of Genes

Fine structure analysis is another important tool in microbial genetics. This method allows scientists to examine the internal organization of genes with high precision, revealing details that traditional mapping techniques can’t provide.

How Fine Structure Analysis Works

Using recombination to break down genes into smaller components, scientists can induce mutations in specific regions of a gene and study how these mutations interact with one another. This process, developed by Seymour Benzer in the 1950s, showed that genes are not simple, indivisible units but rather complex structures with multiple functional regions.

Why Fine Structure Analysis is Important

This method has expanded our understanding of how genes are organized and function, providing valuable insights into gene expression, mutation, and the evolution of genetic structures. Fine structure analysis continues to be a critical tool in both basic research and applied genetic engineering.

Conclusion: The Power of Genetic Transfers in Bacteria

Bacteria have evolved sophisticated mechanisms—transformation, conjugation, transduction, and sex-duction—to transfer genetic material, which not only boosts their own survival but also allows them to share key traits like antibiotic resistance across populations. Understanding these processes gives us insights into bacterial evolution and the rise of antibiotic resistance, while also providing powerful tools for genetic research and biotechnology.

Techniques like interrupted mating and fine structure analysis have been fundamental in unraveling the genetic blueprints of bacteria, helping scientists map genes and decode their function. As we continue to explore the hidden world of microbial genetics, we unlock new possibilities for medical treatments, agricultural improvements, and the ongoing fight against bacterial infections.