When Gregor Mendel first started experimenting with pea plants in the 1800s, he uncovered the basic rules of genetic inheritance that we now call Mendelian principles. His work revolutionized our understanding of how traits get passed down from parents to offspring. According to Mendel, traits are determined by single genes that come in two forms—dominant or recessive. This model helped lay the foundation of genetics, but as scientists dug deeper, they realized things weren’t as simple as Mendel thought.

In reality, inheritance is far more complex, and the way genes interact can result in a fascinating array of outcomes. Today, we understand that there are many extensions to Mendel’s rules that help explain the vast genetic diversity seen in humans and other living organisms. In this blog, we’ll explore these intriguing genetic concepts, including codominance, incomplete dominance, gene interactions, pleiotropy, genomic imprinting, penetrance and expressivity, phenocopy, linkage and crossing over, sex linkage, and sex-limited and sex-influenced traits.

Let’s dive in and explore how these genetic phenomena work, breaking it all down in a way that’s easy to understand.

Codominance: When Both Alleles Share the Spotlight

In codominance, both alleles in a gene pair are fully expressed, and neither one overshadows the other. This is a departure from Mendel’s idea that one allele is always dominant while the other is recessive.

Example: Human Blood Types

A great example of codominance is found in human blood types. If someone inherits an IA allele from one parent and an IB allele from the other, they will have type AB blood. In this case, both the A and B antigens are equally expressed on the surface of the red blood cells, and neither dominates the other. So, instead of having just type A or type B blood, they have both.

This shows how some traits can be equally expressed rather than one being dominant over the other, adding an extra layer of complexity to inheritance.

|

| PROFESSOR LEANDRO A. FREIRE, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Incomplete Dominance: The Art of Blending Traits

While codominance gives equal weight to both alleles, incomplete dominance is like blending the colors of two traits together. Neither allele is completely dominant, so the resulting phenotype is a mix of both.

Example: Snapdragons' Flower Colors

In snapdragons, if you cross a red-flowered plant (RR) with a white-flowered plant (WW), you don’t get all red flowers like you might expect. Instead, you get pink flowers. This pink color is an intermediate trait, blending red and white together because neither allele fully dominates the other.

This example challenges the classical view of inheritance by showing that traits can combine to create something new, rather than one simply overpowering the other.

|

| Attribution- Sciencia58, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons |

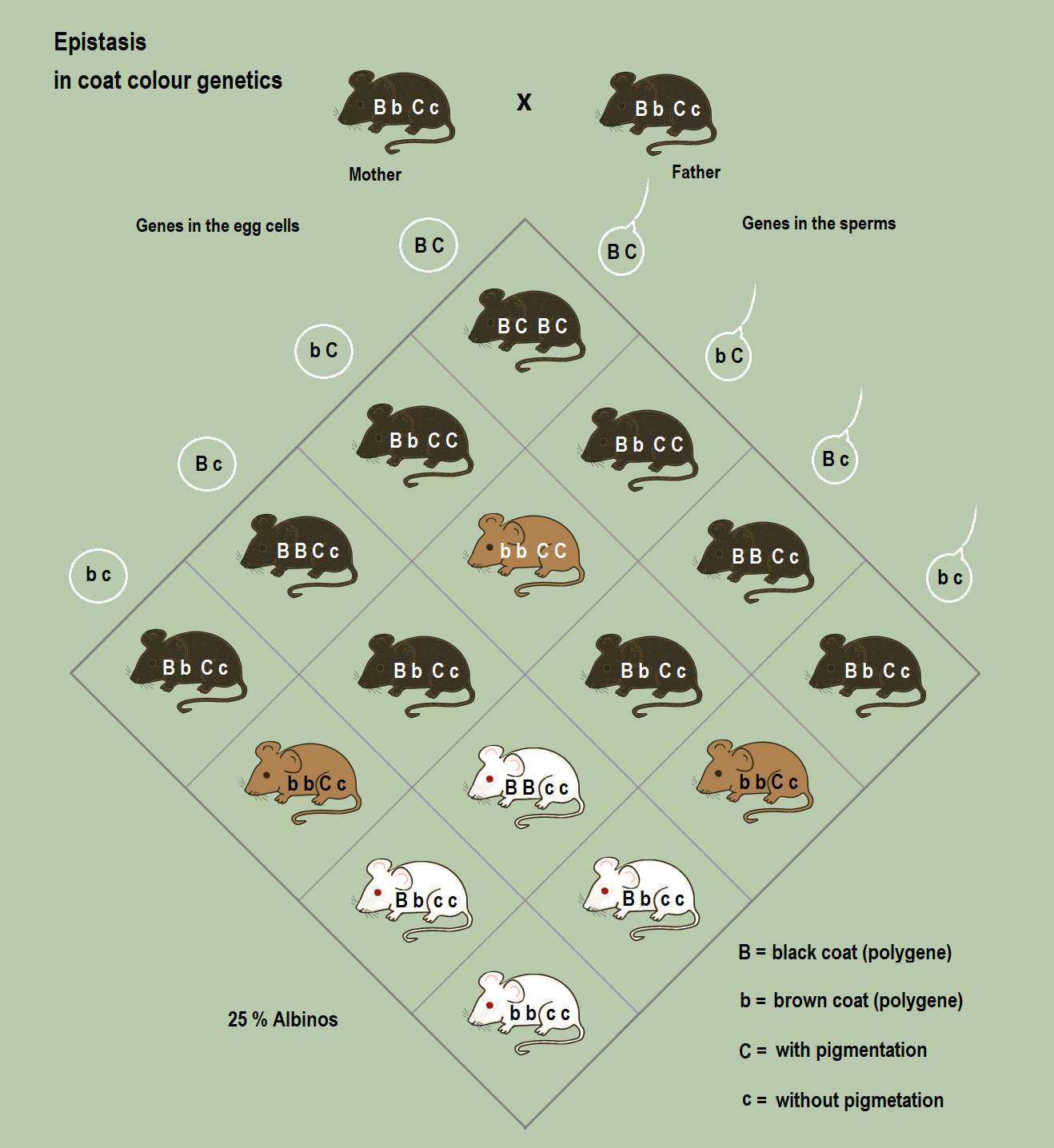

Gene Interactions: When Genes Team Up

Gene interactions occur when two or more genes work together to influence a trait. One common type of gene interaction is epistasis, where one gene can mask or modify the effect of another gene. This is a key player in explaining why some traits don’t follow the classic Mendelian rules.

Example: Labrador Retrievers' Coat Color

In Labrador retrievers, coat color is controlled by two genes: one for pigment color (black or brown) and another for pigment deposition. Even if a dog has the gene for black fur, it might appear yellow if it also has a recessive gene that blocks the deposition of the pigment. This happens because the second gene can “override” the first, masking its effect and producing a different phenotype.

Gene interactions like this show that multiple genes can collaborate to create unexpected outcomes, adding even more depth to how traits are inherited.

|

| Attribution- Sciencia58, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons |

Pleiotropy: One Gene, Many Effects

Pleiotropy occurs when a single gene affects multiple traits in different parts of the body. This is a far cry from the idea that one gene only controls one trait, as Mendel initially suggested.

Example: Marfan Syndrome

A striking example of pleiotropy is Marfan syndrome, a genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the FBN1 gene. This single mutation leads to a variety of symptoms, including long limbs, heart problems, and eye issues. One gene is responsible for all these different effects because it affects a protein that’s critical for connective tissue throughout the body.

Pleiotropy shows how complex gene functions can be, with one gene influencing multiple traits in surprising ways.

|

| Attribution: NettaBaram, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Genomic Imprinting: The Parent's Influence Matters

In genomic imprinting, whether a gene is expressed depends on whether it was inherited from the mother or the father. This adds an interesting twist, as the same gene can have different effects based on its parental origin.

Example: Prader-Willi and Angelman Syndromes

Prader-Willi syndrome and Angelman syndrome both result from deletions in the same region of chromosome 15, but the outcome depends on which parent the defective gene comes from. If the mutation comes from the father, the child develops Prader-Willi syndrome. If it comes from the mother, the result is Angelman syndrome. This is an excellent illustration of how imprinting can influence the expression of a gene and lead to vastly different conditions.

Penetrance and Expressivity: The Spectrum of Gene Expression

Even if you have the genes for a certain trait, it doesn’t always mean you’ll express it. That’s where penetrance and expressivity come into play.

- Penetrance refers to the proportion of individuals with a particular genotype who actually show the expected phenotype. In incomplete penetrance, not everyone with the gene expresses the trait.

- Expressivity measures how strongly a trait is expressed in individuals. Even people with the same genotype can show different degrees of the same trait, a concept known as variable expressivity.

Example: Polydactyly (Extra Fingers or Toes)

Polydactyly, a condition where individuals have extra fingers or toes, can show both incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity. Some people with the gene for polydactyly might not have any extra digits at all (incomplete penetrance), while others may have extra digits that vary in size and functionality (variable expressivity).

These concepts show that gene expression can be influenced by other factors, making it harder to predict how a trait will manifest.

|

| Attribution: Baujat G, Le Merrer M., CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Phenocopy: When the Environment Mimics Genetics

A phenocopy occurs when environmental factors cause a trait that mimics a genetic condition, even though the underlying cause is not genetic.

Example: Thalidomide-Induced Limb Defects

In the 1960s, the drug thalidomide was prescribed to pregnant women to alleviate morning sickness. Unfortunately, it led to severe limb malformations in babies, a condition that looks very similar to a genetic disorder called phocomelia. However, this was a phenocopy because the cause was environmental (thalidomide), not genetic.

This shows that the environment can sometimes mimic the effects of genes, leading to similar outcomes through completely different pathways.

|

| Attribution: Dabs, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Linkage and Crossing Over: Genes That Stick Together

Mendel assumed that genes assort independently, but we now know that genes located close to each other on the same chromosome tend to be inherited together. This phenomenon is called linkage. However, during meiosis, chromosomes can exchange genetic material in a process known as crossing over, which breaks up the linkage and creates new combinations of traits.

Example: Linked Genes in Fruit Flies

In fruit flies, certain traits like eye color and wing shape are often inherited together because the genes controlling these traits are located close to each other on the same chromosome. However, crossing over during meiosis can separate these linked genes, leading to new combinations of traits that weren’t expected based on Mendel’s rules.

Sex Linkage: Traits on the X and Y Chromosomes

Sex-linked traits are those that are carried on the sex chromosomes (X or Y). Since males have one X and one Y chromosome, and females have two X chromosomes, the inheritance of these traits can vary between sexes.

Example: Hemophilia

Hemophilia is a blood clotting disorder that is more common in males because it is an X-linked recessive trait. Since males only have one X chromosome, they are more likely to express the disorder if they inherit the defective gene. Females, on the other hand, would need to inherit two defective X chromosomes to express the trait.

Sex-linked inheritance shows how a trait’s expression can be influenced by the sex of the individual.

Sex-Limited and Sex-Influenced Traits: Genes and Hormones at Work

Some traits are influenced by sex hormones, even though the genes for the trait exist in both males and females.

- Sex-limited traits are traits that only appear in one sex, even though both sexes carry the gene.

- Sex-influenced traits are traits that are expressed differently in males and females due to hormonal differences.

Example: Male Pattern Baldness

Male pattern baldness is a sex-influenced trait. Both men and women can carry the gene for baldness, but it is more common in men because of the influence of male hormones (androgens). Women with the same gene are less likely to go completely bald, though they might experience some hair thinning.

These traits show how hormones and genes work together to influence phenotypes, often in surprising ways.

Conclusion: Genetics Is More Complex Than We Thought

Mendel’s discoveries were groundbreaking, but they only scratched the surface of how traits are inherited. Codominance, incomplete dominance, gene interactions, pleiotropy, genomic imprinting, penetrance and expressivity, phenocopy, linkage and crossing over, sex linkage, and sex-limited and sex-influenced traits reveal the intricate complexity of genetic inheritance. Together, these extensions of Mendelian principles help us understand the rich variety of life’s forms and functions.

In the end, genetics is a beautifully complex web of interactions between genes, chromosomes, and the environment, and we’re still learning more about how it all works every day.