The word cardiovascular is synonymous with circulatory. It pertains to the heart, blood vessels, and blood and, therefore, is related to the distribution of oxygen, hormones, nutrients, and cellular waste within the body. The structure and function of the heart — the subject of this chapter — are essential aspects of human physiology because without the heart to serve as a pump, those things could not be moved through the bloodstream and, therefore, throughout the body to sustain life through the body's tissues. This blog post elucidates the theory behind myogenic hearts and specialized cardiac tissues, the principles and importance of ECG, phases of the cardiac cycle, the heart as a pump, regulation of blood pressure, and neural and chemical regulation in those processes, and finally shows examples of those regulatory mechanisms.

Comparative Anatomy of Heart Structure

The heart has undergone several evolutionary processes among species to befit different physiological demands.

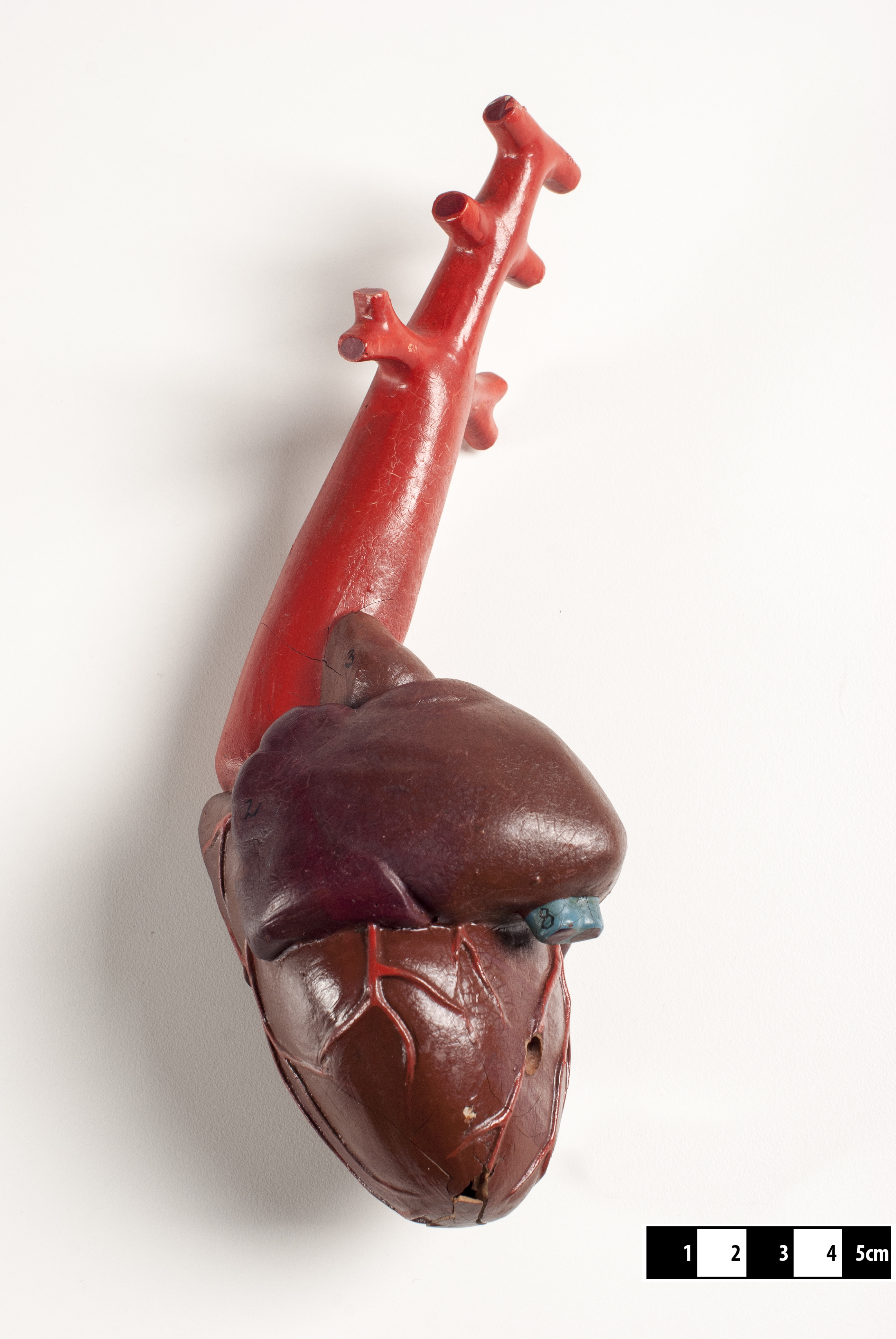

In fish, the heart consists of two principal components that is an atrium and a ventricle. This simple structure holds the single circulation loop where blood is pumped to the gills to get oxygenated before circulation in the body.

|

| Attribution: Wagner Souza e Silva / Museum of Veterinary Anatomy FMVZ USP, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

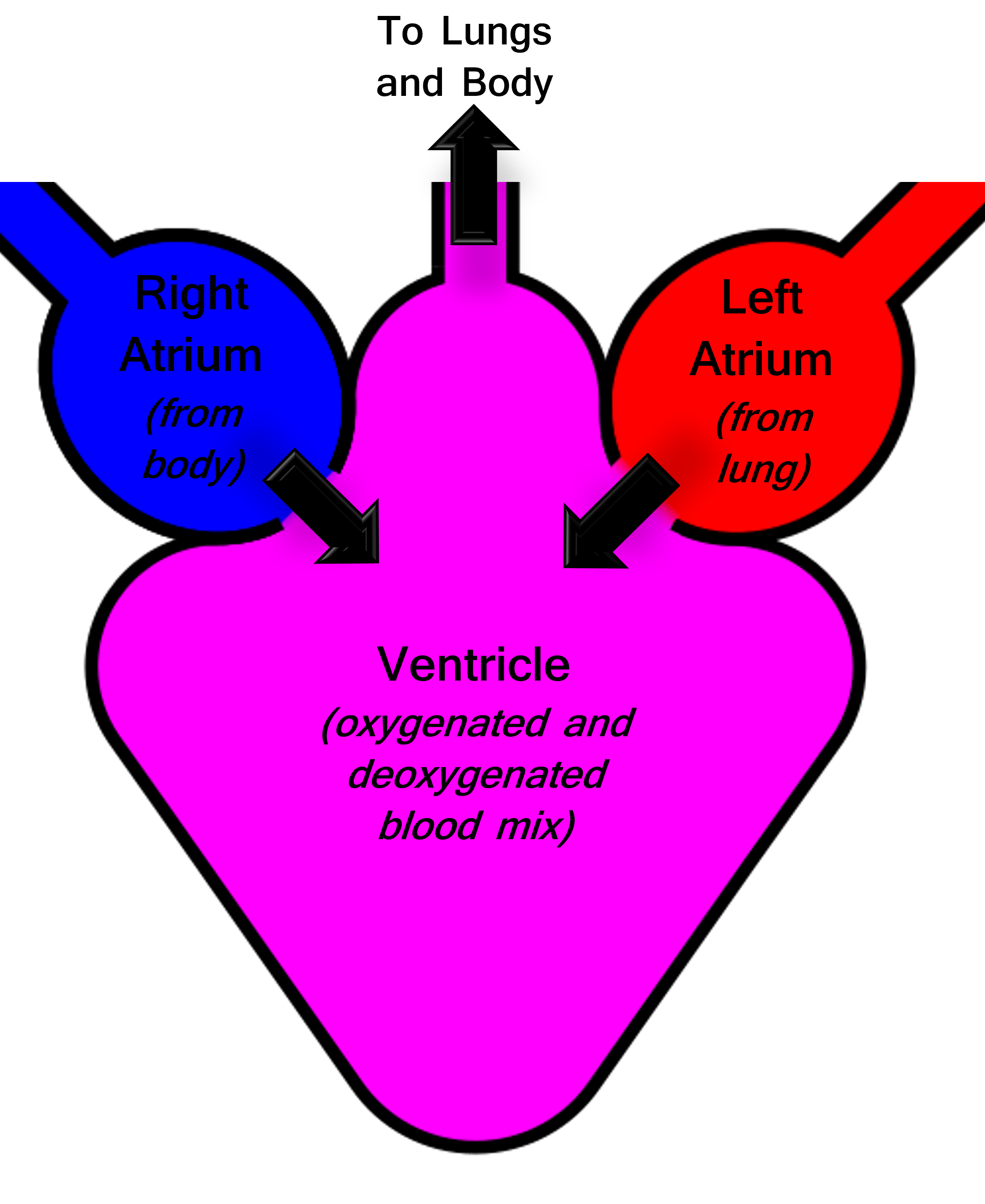

Amphibians have a three-chambered heart, again like that of fish. However, one of the ventricles is only partially divided to allow a partial separation of the oxygenated and deoxygenated blood in the heart. Such an arrangement provides for a double circulatory system of the blood in amphibians with some mixing of the two types of blood in one ventricle.

|

| Attribution: Jon Houseman, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Attribution- SrKellyOP, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons |

In reptiles, a three-chambered heart features a partially divided ventricle to eliminate mixing more effectively.

However, crocodilians have the four-chambered hearts of birds and mammals, where oxygenated and deoxygenated blood is separately handled for systemic and pulmonary circulation. Most structurally advanced hearts are of birds and mammals; they have four-chambered hearts with two atria and two ventricles. Separating two circulations guarantees a high efficiency of blood oxygenation and distribution to organs with high metabolic rates. The adaptive radiation of heart structures across different species underlines the increase in complexity and efficiency of the cardiovascular system, such that it conforms to the metabolic needs of the organisms.

_la.svg.png) |

| Attribution: Wapcaplet et al., CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Myogenic Heart

A myogenic heart is one where the heartbeat is initiated and regulated by specialized cardiac muscle cells rather than by nervous input. In contrast to neurogenic hearts, which rely on external nerve impulses to beat, myogenic hearts can generate their rhythmic contractions.

In myogenic hearts, the sinoatrial (SA) node, often called the natural pacemaker, initiates the electrical impulses that cause the heart to beat. These impulses then travel through the atrioventricular (AV) node, the bundle of His, and Purkinje fibres, coordinating the contraction of the atria and ventricles. This intrinsic ability to generate a heartbeat is essential for maintaining consistent cardiac function and is seen in vertebrates, including humans. The autonomy of myogenic hearts provides a robust mechanism for sustaining life, even without direct nervous system input, making it a crucial feature in higher organisms.

Specialized Cardiac Tissue

The heart contains several specialized tissues that play vital roles in maintaining its function. The sinoatrial (SA) node, located in the right atrium, acts as the heart's pacemaker, generating electrical impulses that set the rate and rhythm of the heartbeat. The atrioventricular (AV) node, situated between the atria and ventricles, serves as a gateway that slows down the electrical signal before it passes to the ventricles, ensuring that the atria have time to contract fully before the ventricles do.

The bundle of His and Purkinje fibres are specialized conductive pathways that rapidly transmit impulses throughout the ventricles, ensuring a coordinated contraction. These tissues are characterized by their unique histological features, such as a high density of gap junctions, which facilitate the rapid spread of electrical impulses, and a distinct cellular architecture adapted for efficient conduction.

Understanding the roles and characteristics of these specialized tissues is crucial for diagnosing and treating cardiac disorders that arise from disruptions in the heart's electrical conduction system.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) – Principle and Significance

An electrocardiogram (ECG) is a diagnostic tool used to assess the electrical activity of the heart. It works by placing electrodes on the skin, which detects the electrical impulses generated by the heart as it beats. These impulses are then recorded and displayed as waves on a graph.

The key components of an ECG wave include the P wave, representing atrial depolarization; the QRS complex, indicating ventricular depolarization; and the T wave, corresponding to ventricular repolarization. By analyzing these components, clinicians can infer various aspects of heart function, such as heart rate, rhythm, and the presence of any abnormalities.

ECG interpretation is crucial for diagnosing a range of cardiac conditions, including arrhythmias, myocardial infarctions, and electrolyte imbalances. For instance, an elevated ST segment may indicate a myocardial infarction, while prolonged QT intervals can be a sign of electrolyte disturbances or medication effects. The clinical significance of the ECG lies in its ability to provide a non-invasive, real-time assessment of the heart's electrical activity, guiding the diagnosis and management of cardiovascular diseases.

The cardiac cycle consists of a series of mechanical and electrical events that occur with each heartbeat, enabling the heart to pump blood effectively. It is divided into two main phases: systole and diastole.

During systole, the ventricles contract, propelling blood into the aorta and pulmonary artery. This phase begins with ventricular depolarization, represented by the QRS complex on an ECG, and includes the first heart sound (S1), caused by the closure of the atrioventricular valves (mitral and tricuspid).

Diastole follows, during which the ventricles relax and fill with blood from the atria. This phase begins with ventricular repolarization, indicated by the T wave on an ECG, and includes the second heart sound (S2), resulting from the closure of the semilunar valves (aortic and pulmonary).

The coordination of these phases ensures efficient blood flow and is tightly regulated by electrical impulses generated within the heart. The relationship between the ECG and the cardiac cycle is fundamental in understanding heart function and diagnosing cardiac conditions.

|

| Attribution: DataBase Center for Life Science (DBCLS), CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Attribution- Created by Agateller (Anthony Atkielski), converted to svg by atom., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Heart as a Pump

The heart functions as a highly efficient pump, working continuously to circulate blood throughout the body. This pumping action is driven by the coordinated contraction of the atria and ventricles.

The atria receive blood from the body and lungs and contract to fill the ventricles. The ventricles then contract forcefully to eject blood into the systemic and pulmonary circulations. The left ventricle, with its thicker muscular wall, pumps oxygenated blood into the systemic circulation, while the right ventricle sends deoxygenated blood to the lungs for oxygenation.

Cardiac output, the volume of blood pumped by the heart per minute, is influenced by heart rate and stroke volume (the amount of blood ejected with each beat). Factors such as preload (the initial stretching of cardiac myocytes), afterload (the resistance the heart must overcome to eject blood), and contractility (the strength of myocardial contraction) all play critical roles in determining cardiac output.

Understanding the heart's function as a pump is essential for diagnosing and managing conditions such as heart failure, where the heart's ability to pump effectively is compromised.

|

| Attribution: DrJanaOfficial, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure is the force exerted by circulating blood on the walls of blood vessels. It is measured in millimetres of mercury (mmHg) and recorded as two values: systolic pressure (the pressure during ventricular contraction) and diastolic pressure (the pressure during ventricular relaxation).

Several factors influence blood pressure, including cardiac output, blood volume, resistance of the blood vessels, and the elasticity of arterial walls.

Cardiac output, which is the amount of blood the heart pumps per minute, directly affects blood pressure. An increase in cardiac output, such as during exercise, raises blood pressure, while a decrease in cardiac output lowers it. Blood volume also impacts blood pressure; greater blood volume results in higher pressure due to the increased fluid load within the vascular system.

The resistance of blood vessels, particularly the arterioles, plays a crucial role in regulating blood pressure. Vasoconstriction (narrowing of blood vessels) increases resistance and, consequently, blood pressure, whereas vasodilation (widening of blood vessels) decreases resistance and blood pressure. The elasticity of arterial walls is another significant factor. Healthy, elastic arteries can expand and contract easily, accommodating changes in blood pressure. However, stiff or hardened arteries, often due to atherosclerosis, can lead to higher blood pressure and increased workload on the heart.

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a condition where blood pressure remains consistently elevated. It is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, including heart attack, stroke, and heart failure. Causes of hypertension include genetic predisposition, obesity, high salt intake, lack of physical activity, and chronic stress. Managing hypertension typically involves lifestyle modifications such as dietary changes, regular exercise, weight management, and, if necessary, medication.

Hypotension, or low blood pressure, is when blood pressure is too low to deliver adequate blood flow to the body's organs. While often less concerning than hypertension, severe hypotension can lead to dizziness, fainting, and in extreme cases, shock. Causes of hypotension include dehydration, severe infection (sepsis), blood loss, and certain medications. Treatment focuses on addressing the underlying cause, such as rehydration or adjusting medication.

Maintaining healthy blood pressure is vital for overall cardiovascular health. Regular monitoring, a balanced diet low in salt and rich in fruits and vegetables, regular physical activity, maintaining a healthy weight, and managing stress are key strategies for preventing and controlling blood pressure abnormalities. Understanding the dynamics of blood pressure and its regulation is crucial for diagnosing and treating related conditions effectively.

|

| Attribution- rawpixel.com, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons |