Imagine being able to zoom in on a single molecule within a cell, finding it in a sea of billions of other particles. It sounds like something out of science fiction, but it’s precisely what histochemistry and immune techniques allow scientists to do. These powerful methods use the natural specificity of antibodies and advanced detection techniques to pinpoint, visualize, and study molecules within cells and tissues.

In this blog, we’ll explore how immune techniques—like ELISA, western blotting, and immunofluorescence microscopy—are applied across scientific fields. Whether it’s diagnosing disease, tracking cellular changes, or unraveling genetic mysteries, these tools are helping scientists uncover the details that define the complex inner workings of life itself.

Antibody Generation: Building Blocks of Precision Detection

At the core of most immune techniques lies the antibody—a protein that the immune system creates to recognize and bind to foreign substances (antigens). Scientists harness this natural precision by generating antibodies that target specific molecules, enabling them to detect, visualize, or isolate these molecules in complex samples.

Creating Antibodies for Research

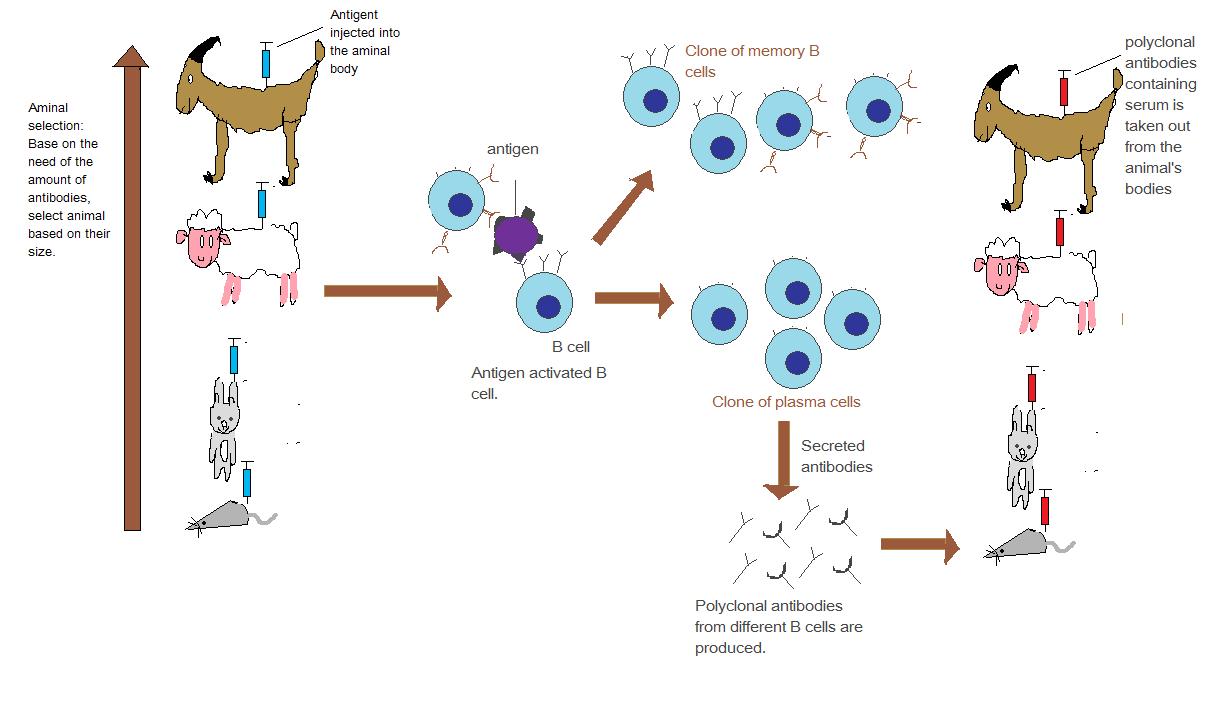

To generate antibodies, researchers introduce the molecule of interest (the antigen) into an animal’s immune system, often using rabbits or mice. The animal’s immune response produces antibodies designed to recognize and bind specifically to that molecule. These antibodies are then extracted and purified, becoming invaluable tools for scientific research and diagnostics.

There are two main types of antibodies:

- Polyclonal Antibodies: Produced by different immune cells, these recognize multiple sites on the antigen, making them versatile but less specific.

|

| Attribution: Gentaur, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

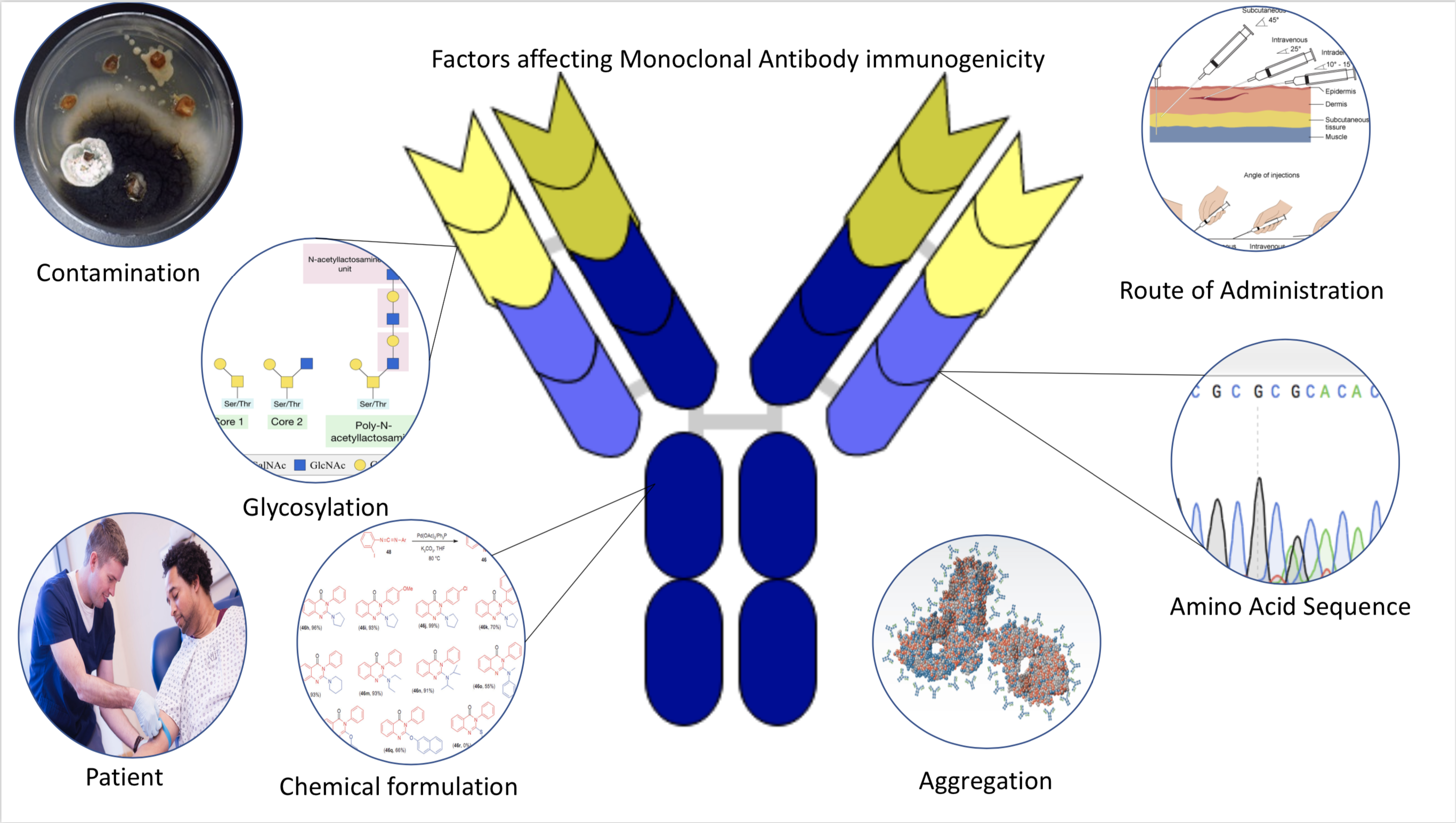

- Monoclonal Antibodies: Created from a single immune cell line, these are highly specific and bind to one unique site on the antigen, offering exceptional precision.

|

| Attribution- Lizanne Koch, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Antibodies form the foundation of countless techniques in molecular biology and medical diagnostics, making them indispensable in modern research.

ELISA: Detecting Molecules with Color

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is one of the most widely used methods for detecting and measuring specific molecules, such as proteins, hormones, or antibodies, in a sample. ELISA is fast, highly sensitive, and widely used in both research and medical diagnostics—from identifying viruses in blood to detecting antibodies after vaccination.

How ELISA Works

In ELISA, the sample is added to a plate coated with an antibody specific to the molecule of interest. If the molecule (antigen) is present, it binds to the antibody. A second enzyme-linked antibody then binds to the antigen, and a substrate is added that changes color, signaling the presence and quantity of the target molecule.

Types of ELISA

- Direct ELISA: A single antibody directly linked to an enzyme detects the antigen.

- Indirect ELISA: A primary antibody captures the antigen, and a secondary enzyme-linked antibody detects it.

- Sandwich ELISA: A “capture” antibody on the plate binds to the antigen, and another labeled antibody detects it. This method is ideal for detecting larger molecules.

Because of its precision, ELISA is a go-to tool for scientists who need to quantify molecules accurately, from proteins in research studies to biomarkers in clinical tests.

RIA: Measuring Tiny Quantities with Radiolabeling

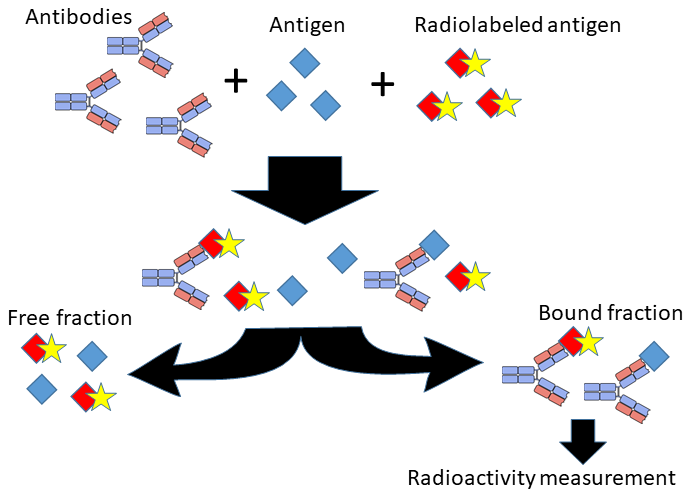

Radioimmunoassay (RIA) is another method for detecting and quantifying specific molecules, such as hormones or drugs, often at very low concentrations. Unlike ELISA, which relies on enzymes for detection, RIA uses radioactive labeling, making it exceptionally sensitive.

How RIA Works

In RIA, a sample with an unknown amount of antigen competes with a known amount of radiolabeled antigen to bind to an antibody. By measuring the radioactivity of the resulting complex, scientists can calculate the amount of the antigen in the sample.

Because of its sensitivity, RIA is useful for detecting trace amounts of molecules, although the use of radioactive materials requires strict safety protocols.

|

| Attribution- Mikael Häggström, M.D. Author info - Reusing images- Conflicts of interest: NoneMikael Häggström, M.D., CC0, via Wikimedia Commons |

Western Blot: Separating and Identifying Proteins

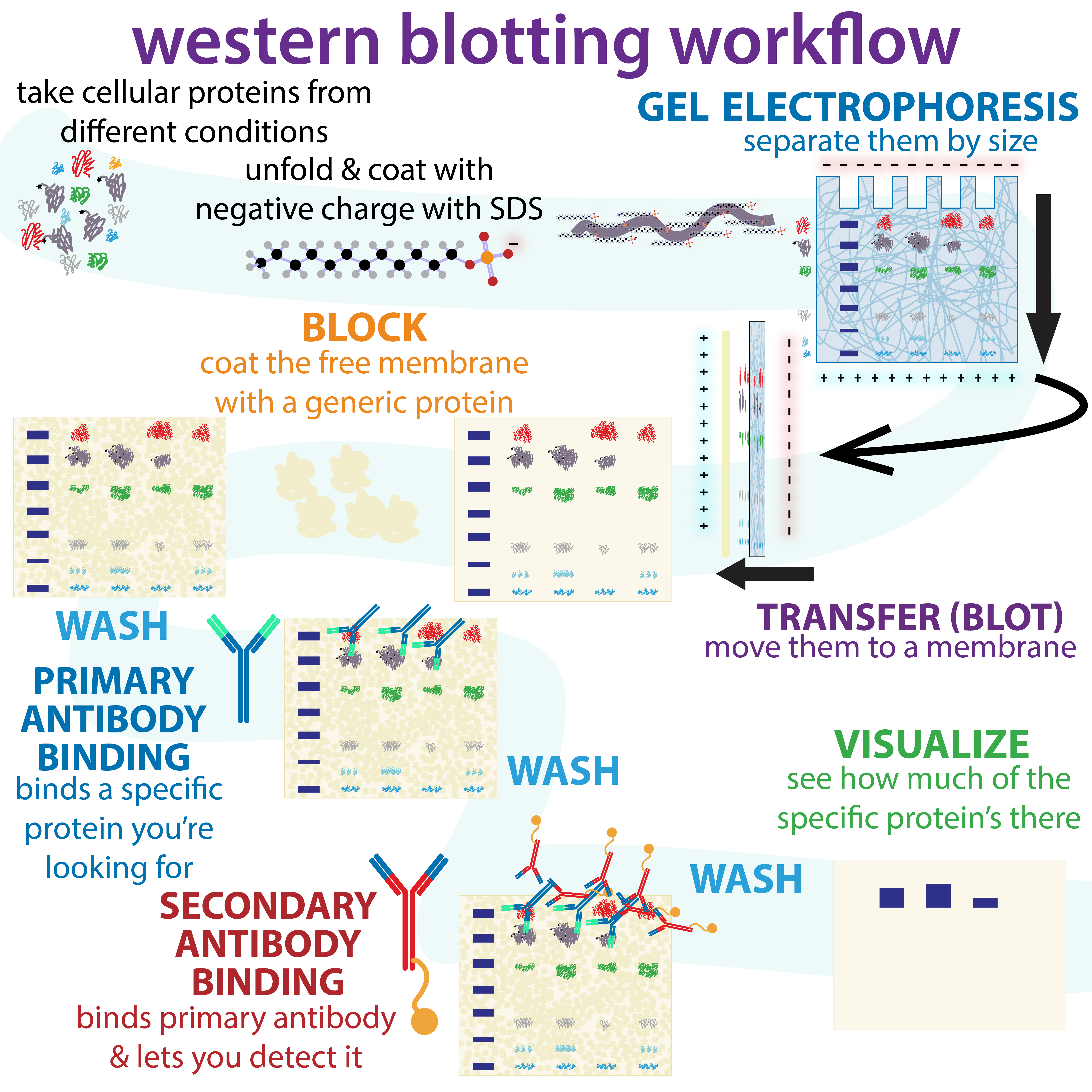

Western blotting is a widely used technique for identifying and analyzing proteins in complex mixtures. This method separates proteins based on their molecular weight, helping researchers verify the presence of specific proteins and understand changes in protein expression.

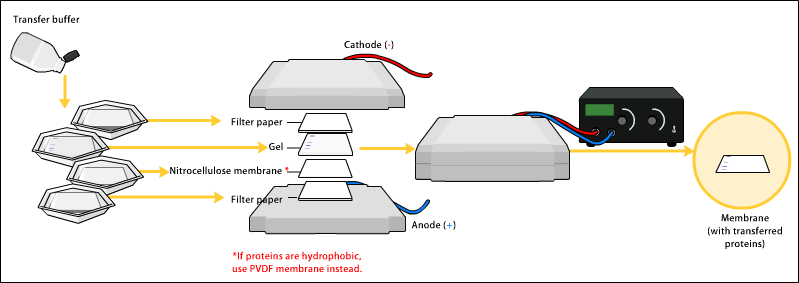

How Western Blot Works

Proteins in the sample are separated by gel electrophoresis, which sorts them by size. The proteins are then transferred to a membrane and exposed to antibodies that bind to the target protein. A secondary antibody with a detectable label (often an enzyme or fluorescent marker) binds to the primary antibody, visualizing the protein as distinct bands.

.jpg) |

| Attribution: NIAID, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Western blotting is an essential tool in studying disease markers, protein expression, and molecular signaling pathways, making it a staple in molecular biology labs.

|

| Attribution: Biochemlife, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Attribution: Bensaccount at English Wikipedia, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Immunoprecipitation: Isolating Specific Proteins

Immunoprecipitation (IP) is a technique used to “pull out” specific proteins from a complex sample, enabling scientists to study the protein in isolation or investigate its interactions with other molecules. It’s particularly useful for analyzing protein function, studying protein modifications, and examining protein-protein interactions.

How Immunoprecipitation Works

A specific antibody is added to a sample containing the protein of interest. When the antibody binds to the target protein, beads are added to capture the antibody-protein complex. This allows researchers to “precipitate” the complex, which can then be separated and analyzed further.

Immunoprecipitation is key for studying cellular interactions and signaling pathways, helping researchers understand complex biological processes.

|

| Fig.- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Attribution- Jkwchui, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Flow Cytometry: Analyzing Cells in Motion

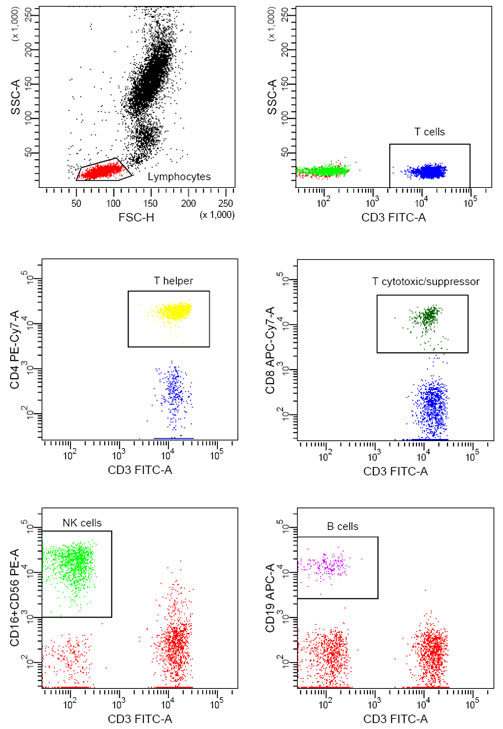

Flow cytometry is a powerful, high-speed technique that analyzes thousands of cells individually, allowing scientists to characterize cell populations based on size, shape, and the presence of specific markers. It’s used in immunology, cancer research, and clinical diagnostics.

How Flow Cytometry Works

Cells in a sample are stained with fluorescent antibodies that bind to specific markers. As cells pass through a laser beam in a single-file stream, they emit light at specific wavelengths. Detectors capture this light, allowing scientists to analyze each cell’s characteristics based on fluorescence.

Flow cytometry is ideal for studying immune cells, sorting cell types, and even detecting cancerous cells, providing valuable information about cell populations in health and disease.

|

| Attribution: Jkwchui, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Attribution: CharlotteHayden, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

Immunofluorescence Microscopy: Lighting Up Cells and Tissues

Immunofluorescence microscopy uses the specificity of antibodies combined with fluorescence to visualize molecules within cells or tissues. This technique allows scientists to observe where proteins and other molecules are located, providing insights into cellular structure and function.

|

| Attribution: Caliandrea, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

How Immunofluorescence Works

Fluorescently-labeled antibodies bind to specific molecules in the cells or tissue samples. When viewed under a fluorescence microscope, these labeled molecules emit light, creating detailed images that reveal the cellular location of the target molecules.

Immunofluorescence is invaluable for studying the spatial arrangement of proteins, revealing insights into cellular architecture and dynamic processes within living cells.

|

| Attribution: Mirna Jarovic, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons |

Detection in Living Cells: Real-Time Insights

In recent years, scientists have developed methods to detect molecules in living cells, allowing them to track cellular processes in real time. Techniques like live-cell imaging and fluorescent protein tagging enable researchers to watch proteins move, interact, and respond to changes within living cells.

Real-time analysis in living cells has transformed our understanding of dynamic processes such as cell division, signal transduction, and gene expression, providing insights that are impossible to achieve with fixed cells or tissue samples.

In Situ Localization: Finding Molecules in Their Native Environment

In situ localization techniques allow scientists to detect and locate specific molecules in their natural cellular or tissue environments, helping to map gene expression and chromosomal organization.

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

FISH uses fluorescent probes to bind to specific DNA or RNA sequences, making it possible to visualize specific genes on chromosomes. FISH is frequently used in diagnostics for chromosomal abnormalities, cancer research, and gene expression studies..jpg)

Attribution: MrMatze, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Genomic In Situ Hybridization (GISH)

GISH is a version of FISH used primarily in plant genetics to distinguish genomes within hybrid species. It’s often applied in studies of gene transfer and chromosomal inheritance in hybrid plants.

These in situ techniques offer a powerful way to observe genes, chromosomes, and other molecules within the intact cellular or tissue structure, providing insights into their natural arrangement and activity.

Conclusion: How Immunotechniques and Histochemistry are Changing Science

The field of histochemistry and immunotechniques has reshaped molecular biology, offering scientists unmatched precision in studying and visualizing molecules. From detecting single proteins in cells to analyzing thousands of cells per second, these techniques provide a window into the smallest yet most impactful details of life.

As advancements in antibody generation, fluorescence tagging, and live-cell imaging continue to improve, these tools will only grow more precise and powerful. In a world where understanding the tiniest cellular changes can lead to major discoveries, histochemical and immune techniques are invaluable, allowing us to observe and interact with the molecular foundations of life.

These methods are more than just tools—they’re the keys to understanding life’s invisible machinery and uncovering secrets that have the potential to transform medicine, diagnostics, and our understanding of biology itself.